How Is The Atman Related To Animals And Humans

Ātman (; Sanskrit: आत्मन्) is a Sanskrit word that refers to the (universal) Self or self-existent essence of individuals, as distinct from ego (Ahamkara), mind (Citta) and embodied existence (Prakṛti).[notation 1] The term is often translated as soul,[notation 2] merely is ameliorate translated as "Cocky,"[1] as it solely refers to pure consciousness or witness-consciousness, beyond identification with phenomena. In order to accomplish moksha (liberation), a human existence must acquire self-knowledge (Atma Gyaan or Brahmajnana).

Atman is a key concept in the various schools of Indian philosophy, which have different views on the relation between Atman, individual Self (Jīvātman), supreme Self (Paramātmā) and, the Ultimate Reality (Brahman), stating that they are: completely identical (Advaita, Non-Dualist),[two] [3] completely unlike (Dvaita, Dualist), or simultaneously non-unlike and unlike (Bhedabheda, Non-Dualist + Dualist).[four]

The half-dozen orthodox schools of Hinduism believe that there is Ātman in every living existence (jiva), which is distinct from the body-mind complex. This is a major point of deviation with the Buddhist doctrine of Anatta, which holds that in essence there is no unchanging essence or Self to be found in the empirical constituents of a living beingness,[note 3] staying silent on what information technology is that is liberated.[v] [6] [7] [8]

Etymology and significant [edit]

Etymology [edit]

Ātman (Atma, आत्मा, आत्मन्) is a Sanskrit word which refers to "essence, breath."[web 1] [web 2] [ix] It is derived from the Proto-Indo-European word *h₁eh₁tmṓ (a root meaning "breath" with Germanic cognates: Dutch adem, Former High High german atum "breath," Modern German atmen "to breathe" and Atem "respiration, breath", Old English language eþian).[web 2]

Ātman, sometimes spelled without a diacritic as atman in scholarly literature,[ten] means "existent Cocky" of the individual,[notation one] "innermost essence."[11] While often translated as "soul," information technology is better translated as "cocky."[1] [note two]

Meaning [edit]

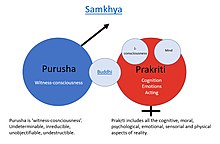

In Hinduism, Atman refers to the self-existent essence of human beings, the observing pure consciousness or witness-consciousness as exemplified by the Purusha of Samkhya. Information technology is distinct from the ever-evolving embodied individual being (jivanatman) embedded in material reality, exemplified by the prakriti of Samkhya, and characterized by Ahamkara (ego, not-spiritual psychological I-ness Me-ness), mind (citta, manas), and all the defiling kleshas (habits, prejudices, desires, impulses, delusions, fads, behaviors, pleasures, sufferings and fears). Embodied personality and Ahamkara shift, evolve or change with time, while Atman doesn't.[12] It is "pure, undifferentiated, cocky-shining consciousness."[13]

As such, it is dissimilar from non-Hindu notions of soul, which includes consciousness but also the mental abilities of a living being, such every bit reason, character, feeling, consciousness, memory, perception and thinking. In Hinduism, these are all included in embodied reality, the counterpart of Atman.

Atman, in Hinduism, is considered equally eternal, imperishable, beyond fourth dimension, "not the same equally body or mind or consciousness, but... something beyond which permeates all these".[14] [fifteen] [16] Atman is the unchanging, eternal, innermost radiant Cocky that is unaffected by personality, unaffected past ego; Atman is that which is always-free, never-jump, the realized purpose, meaning, liberation in life.[17] [18] Equally Puchalski states, "the ultimate goal of Hindu religious life is to transcend individually, to realize one'southward own true nature", the inner essence of oneself, which is divine and pure.[19]

Evolution of the concept [edit]

Vedas [edit]

The earliest use of the discussion Ātman in Indian texts is found in the Rig Veda (RV 10.97.11).[20] Yāska, the ancient Indian grammarian, commenting on this Rigvedic verse, accepts the following meanings of Ātman: the pervading principle, the organism in which other elements are united and the ultimate sentient principle.[21]

Other hymns of Rig Veda where the word Ātman appears include I.115.1, VII.87.2, 7.101.six, Viii.three.24, 9.2.10, 9.6.eight, and X.168.4.[22]

Upanishads [edit]

Ātman is a key topic in all of the Upanishads, and "know your Ātman" is 1 of their thematic foci.[23] The Upanishads say that Atman denotes "the ultimate essence of the universe" as well equally "the vital jiff in human beings", which is "imperishable Divine within" that is neither born nor does it die.[24] Cosmology and psychology are duplicate, and these texts land that the core of every person's Self is not the torso, nor the mind, nor the ego, only Ātman. The Upanishads express two distinct, somewhat divergent themes on the relation betwixt Atman and Brahman. Some teach that Brahman (highest reality; universal principle; being-consciousness-elation) is identical with Ātman, while others teach that Ātman is function of Brahman simply not identical to it.[25] [26] This ancient argue flowered into various dual and non-dual theories in Hinduism. The Brahmasutra by Badarayana (~100 BCE) synthesized and unified these somewhat conflicting theories, stating that Atman and Brahman are unlike in some respects, especially during the state of ignorance, but at the deepest level and in the state of self-realization, Atman and Brahman are identical, non-different (advaita).[25] According to Koller, this synthesis countered the dualistic tradition of Samkhya-Yoga schools and realism-driven traditions of Nyaya-Vaiseshika schools, enabling it to get the foundation of Vedanta as Hinduism'south near influential spiritual tradition.[25]

Brihadaranyaka Upanishad [edit]

The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (800-600 BCE[27]) describes Atman as that in which everything exists, which is of the highest value, which permeates everything, which is the essence of all, bliss and across description.[28] In hymn 4.iv.5, Brihadaranyaka Upanishad describes Atman every bit Brahman, and associates information technology with everything one is, everything one tin be, one's complimentary will, ane'southward desire, what one does, what one doesn't exercise, the adept in oneself, the bad in oneself.

That Atman (self, soul) is indeed Brahman. It [Ātman] is likewise identified with the intellect, the Manas (mind), and the vital breath, with the optics and ears, with earth, water, air, and ākāśa (sky), with burn and with what is other than fire, with want and the absence of desire, with anger and the absence of acrimony, with righteousness and unrighteousness, with everything — it is identified, every bit is well known, with this (what is perceived) and with that (what is inferred). As it [Ātman] does and acts, so it becomes: by doing practiced it becomes adept, and by doing evil it becomes evil. It becomes virtuous through practiced acts, and vicious through evil acts. Others, however, say, "The self is identified with desire lone. What it desires, and so it resolves; what it resolves, then is its deed; and what deed it does, so it reaps.

—Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 4.4.5, ninth century BCE[29]

This theme of Ātman, that the essence and Self of every person and being is the same as Brahman, is extensively repeated in Brihadāranyaka Upanishad. The Upanishad asserts that this knowledge of "I am Brahman", and that in that location is no divergence between "I" and "you", or "I" and "him" is a source of liberation, and not fifty-fifty gods can prevail over such a liberated human. For case, in hymn i.4.x,[xxx]

Brahman was this before; therefore information technology knew even the Ātma (soul, himself). I am Brahman, therefore information technology became all. And whoever among the gods had this enlightenment, besides became That. It is the aforementioned with the sages, the same with men. Whoever knows the cocky every bit "I am Brahman," becomes all this universe. Fifty-fifty the gods cannot prevail against him, for he becomes their Ātma. Now, if a homo worships another god, thinking: "He is ane and I am another," he does non know. He is similar an animal to the gods. Every bit many animals serve a human being, so does each man serve the gods. Even if i brute is taken away, it causes ache; how much more than so when many are taken away? Therefore information technology is not pleasing to the gods that men should know this.

—Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 1.four.ten[30]

Chandogya Upanishad [edit]

The Chandogya Upanishad (7th-6th c. BCE) explains Ātman as that which appears to be separate between two living beings but isn't, that essence and innermost, truthful, radiant self of all individuals which connects and unifies all. Hymn 6.10 explains it with the case of rivers, some of which flow to the eastward and some to the west, but ultimately all merge into the ocean and become one. In the same way, the individual souls are pure being, states the Chandogya Upanishad; an individual soul is pure truth, and an individual soul is a manifestation of the ocean of ane universal soul.[31]

Katha Upanishad [edit]

Along with the Brihadāranyaka, all the earliest and eye Upanishads discuss Ātman every bit they build their theories to reply how man can achieve liberation, freedom and bliss. The Katha Upanishad (fifth to 1st century BCE), for example, explains Atman as the imminent and transcendent innermost essence of each man being and living animate being, that this is one, fifty-fifty though the external forms of living creatures manifest in unlike forms. For example, hymn two.2.nine states,

As the one fire, subsequently it has entered the world, though one, takes unlike forms according to whatever it burns, and then does the internal Ātman of all living beings, though i, takes a form according to whatever He enters and is outside all forms.

—Katha Upanishad, 2.ii.9[32]

Katha Upanishad, in Book i, hymns 3.three to 3.4, describes the widely cited proto-Samkhya analogy of chariot for the relation of "Soul, Self" to body, mind and senses.[33] Stephen Kaplan[34] translates these hymns every bit, "Know the Self as the rider in a chariot, and the body as simply the chariot. Know the intellect as the charioteer, and the mind as the reins. The senses, they say are the horses, and sense objects are the paths around them". The Katha Upanishad then declares that "when the Self [Ātman] understands this and is unified, integrated with body, senses and mind, is virtuous, mindful and pure, he reaches bliss, freedom and liberation".[33]

Indian philosophy [edit]

Orthodox schools [edit]

Atman is a metaphysical and spiritual concept for Hindus, often discussed in their scriptures with the concept of Brahman.[35] [36] [37] All major orthodox schools of Hinduism – Samkhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaisesika, Mimamsa, and Vedanta – accept the foundational premise of the Vedas and Upanishads that "Ātman exists." In Hindu philosophy, particularly in the Vedanta school of Hinduism, Ātman is the first principle.[38] Jainism also accepts this premise, although it has its ain thought of what that means. In contrast, both Buddhism and the Charvakas deny that there is anything called "Ātman/soul/self".[12]

Samkhya [edit]

In Samkhya, the oldest school of Hinduism, Puruṣa, the witness-consciousness, is Atman. It is accented, independent, free, ephemeral, unknowable through other agencies, above any experience by mind or senses and beyond whatsoever words or explanations. Information technology remains pure, "nonattributive consciousness". Puruṣa is neither produced nor does it produce.[39] No appellations can qualify purusha, nor can it substantialized or objectified.[forty] It "cannot exist reduced, tin can't exist 'settled'." Any designation of purusha comes from prakriti, and is a limitation.[41] Unlike Advaita Vedanta, and like Purva-Mīmāṃsā, Samkhya believes in plurality of the puruṣas.[39] [12]

Samkhya considers ego (asmita, ahamkara) to be the cause of pleasure and pain.[42] Cocky-knowledge is the ways to attain kaivalya, the separation of Atman from the body-mind complex.[12]

Yoga philosophy [edit]

The Yogasutra of Patanjali, the foundational text of Yoga school of Hinduism, mentions Atma in multiple verses, and particularly in its last book, where Samadhi is described every bit the path to self-knowledge and kaivalya. Some earlier mentions of Atman in Yogasutra include poetry two.5, where evidence of ignorance includes "disruptive what is not Atman every bit Atman".

अनित्याशुचिदुःखानात्मसु नित्यशुचिसुखात्मख्यातिरविद्या

Avidya (अविद्या, ignorance) is regarding the transient equally eternal, the impure as pure, the hurting-giving as joy-giving, and the non-Atman as Atman.

—Yogasutra 2.5[43]

In verses ii.xix-two.twenty, Yogasutra declares that pure ideas are the domain of Atman, the perceivable universe exists to enlighten Atman, simply while Atman is pure, it may be deceived past complexities of perception or listen. These verses also gear up the purpose of all experience as a means to cocky-knowledge.

द्रष्टा दृशिमात्रः शुद्धोऽपि प्रत्ययानुपश्यः

तदर्थ एव दृश्यस्यात्माThe seer is the absolute knower. Though pure, modifications are witnessed by him by coloring of intellect.

The spectacle exists but to serve the purpose of the Atman.—Yogasutra 2.xix - 2.20[43]

In Volume 4, Yogasutra states spiritual liberation equally the phase where the yogin achieves distinguishing cocky-knowledge, he no longer confuses his mind equally Atman, the mind is no longer affected by afflictions or worries of any kind, ignorance vanishes, and "pure consciousness settles in its own pure nature".[43] [44]

The Yoga schoolhouse is similar to the Samkhya school in its conceptual foundations of Ātman. It is the cocky that is discovered and realized in the Kaivalya state, in both schools. Similar Samkhya, this is non a single universal Ātman. Information technology is one of the many individual selves where each "pure consciousness settles in its own pure nature", as a unique distinct soul/self.[45] Nevertheless, Yoga school's methodology was widely influential on other schools of Hindu philosophy. Vedanta monism, for example, adopted Yoga as a ways to reach Jivanmukti – self-realization in this life – every bit conceptualized in Advaita Vedanta. Yoga and Samkhya ascertain Ātman as an "unrelated, attributeless, self-luminous, omnipresent entity", which is identical with consciousness.[24]

Nyaya [edit]

Early atheistic Nyaya scholars, and later theistic Nyaya scholars, both made substantial contributions to the systematic study of Ātman.[46] They posited that even though "self" is intimately related to the knower, it tin still be the subject area of knowledge. John Plott[46] states that the Nyaya scholars adult a theory of negation that far exceeds Hegel'south theory of negation, while their epistemological theories refined to "know the knower" at least equals Aristotle's sophistication. Nyaya methodology influenced all major schools of Hinduism.

The Nyaya scholars divers Ātman as an ephemeral substance that is the substrate of human consciousness, manifesting itself with or without qualities such every bit desires, feelings, perception, noesis, understanding, errors, insights, sufferings, bliss, and others.[47] [48] Nyaya school not just adult its theory of Atman, it contributed to Hindu philosophy in a number of ways. To the Hindu theory of Ātman, the contributions of Nyaya scholars were twofold. One, they went beyond holding information technology as "self evident" and offered rational proofs, consistent with their epistemology, in their debates with Buddhists, that "Atman exists".[49] Second, they developed theories on what "Atman is and is non".[50] Equally proofs for the proposition 'self exists', for example, Nyaya scholars argued that personal recollections and memories of the grade "I did this so many years agone" implicitly presume that there is a self that is substantial, continuing, unchanged, and existent.[49] [50]

Nyayasutra, a 2nd-century CE foundational text of Nyaya schoolhouse of Hinduism, states that Atma is a proper object of human being knowledge. It besides states that Atman is a existent substance that can be inferred from certain signs, objectively perceivable attributes. For example, in volume ane, affiliate 1, verses 9 and 10, Nyayasutra states[47]

Ātman, body, senses, objects of senses, intellect, mind, activity, error, pretyabhava (after life), fruit, suffering and elation are the objects of right cognition.

Want, aversion, try, happiness, suffering and knowledge are the Linga (लिङ्ग, mark, sign) of the Ātman.—Nyaya Sutra, I.1.ix-10[47]

Volume 2, chapter 1, verses 1 to 23, of the Nyayasutras posits that the sensory act of looking is different from perception and knowledge–that perception and knowledge arise from the seekings and actions of Ātman.[51] The Naiyayikas emphasize that Ātman has qualities, but is different from its qualities. For example, desire is ane of many qualities of Ātman, simply Ātman does not always have want, and in the state of liberation, for instance, the Ātman is without desire.[47]

Vaiśeṣika [edit]

The Vaisheshika school of Hinduism, using its non-theistic theories of atomistic naturalism, posits that Ātman is ane of the four eternal non-concrete[52] substances without attributes, the other iii being kala (time), dik (space) and manas (mind).[53] Fourth dimension and space, stated Vaiśeṣika scholars, are eka (i), nitya (eternal) and vibhu (all pervading). Time and space are indivisible reality, but human mind prefers to divide them to comprehend past, present, hereafter, relative place of other substances and beings, direction and its own coordinates in the universe. In contrast to these characteristics of fourth dimension and space, Vaiśeṣika scholars considered Ātman to be many, eternal, independent and spiritual substances that cannot exist reduced or inferred from other three non-physical and v physical dravya (substances).[53] Mind and sensory organs are instruments, while consciousness is the domain of "atman, soul, self".[53]

The knowledge of Ātman, to Vaiśeṣika Hindus, is another noesis without any "bliss" or "consciousness" moksha state that Vedanta and Yoga school describe.[12]

Mimamsa [edit]

Ātman, in the ritualism-based Mīmāṃsā school of Hinduism, is an eternal, omnipresent, inherently active essence that is identified equally I-consciousness.[54] [55] Dissimilar all other schools of Hinduism, Mimamsaka scholars considered ego and Atman equally the same. Within Mimamsa school, in that location was divergence of behavior. Kumārila, for example, believed that Atman is the object of I-consciousness, whereas Prabhakara believed that Atman is the subject area of I-consciousness.[54] Mimamsaka Hindus believed that what matters is virtuous actions and rituals completed with perfection, and it is this that creates merit and imprints cognition on Atman, whether 1 is aware or non enlightened of Atman. Their foremost emphasis was formulation and understanding of laws/duties/virtuous life (dharma) and consequent perfect execution of kriyas (actions). The Upanishadic give-and-take of Atman, to them, was of secondary importance.[55] [56] While other schools disagreed and discarded the Atma theory of Mimamsa, they incorporated Mimamsa theories on ethics, cocky-discipline, action, and dharma equally necessary in i's journey toward knowing one's Atman.[57] [58]

Vedanta [edit]

Advaita Vedanta [edit]

Advaita Vedanta (non-dualism) sees the "spirit/soul/cocky" within each living entity as beingness fully identical with Brahman.[59] The Advaita school believes that there is one soul that connects and exists in all living beings, regardless of their shapes or forms, and at that place is no distinction, no superior, no inferior, no separate devotee soul (Atman), no dissever god soul (Brahman).[59] The oneness unifies all beings, at that place is divine in every being, and that all existence is a single reality, state the Advaita Vedanta Hindus. In contrast, devotional sub-schools of Vedanta such every bit Dvaita (dualism) differentiate between the individual Atma in living beings, and the supreme Atma (Paramatma) as beingness split.[sixty] [61]

Advaita Vedanta philosophy considers Atman as self-existent sensation, limitless and non-dual.[62] To Advaitins, the Atman is the Brahman, the Brahman is the Atman, each self is not-different from the infinite.[59] [63] Atman is the universal principle, one eternal undifferentiated cocky-luminous consciousness, the truth asserts Advaita Hinduism.[64] [65] Human beings, in a state of unawareness of this universal self, encounter their "I-ness" every bit dissimilar from the being in others, and so act out of impulse, fears, cravings, malice, sectionalisation, defoliation, feet, passions, and a sense of distinctiveness.[66] [67] To Advaitins, Atman-knowledge is the land of total awareness, liberation, and freedom that overcomes dualities at all levels, realizing the divine inside oneself, the divine in others, and in all living beings; the non-dual oneness, that God is in everything, and everything is God.[59] [62] This identification of private living beings/souls, or jiva-atmas, with the 'one Atman' is the non-dualistic Advaita Vedanta position.

[edit]

The monist, non-dual conception of existence in Advaita Vedanta is not accepted by the dualistic/theistic Dvaita Vedanta. Dvaita Vedanta calls the Atman of a supreme being as Paramatman, and holds information technology to be different from individual Atman. Dvaita scholars assert that God is the ultimate, complete, perfect, but distinct soul, one that is divide from incomplete, imperfect jivas (individual souls).[68] The Advaita sub-schoolhouse believes that self-knowledge leads to liberation in this life, while the Dvaita sub-schoolhouse believes that liberation is only possible in afterward-life as communion with God, and only through the grace of God (if not, so one's Atman is reborn).[69] God created individual souls, state Dvaita Vedantins, but the individual soul never was and never will become one with God; the best it can exercise is to feel bliss by getting infinitely close to God.[70] The Dvaita school, therefore, in contrast to the monistic position of Advaita, advocates a version of monotheism wherein Brahman is fabricated synonymous with Vishnu (or Narayana), distinct from numerous individual Atmans. The Dvaita school, states Graham Oppy, is not strict monotheism, as information technology does not deny existence of other gods and their respective Atman.[71]

Buddhism [edit]

Applying the disidentification of 'no-cocky' to the logical end,[5] [8] [7] Buddhism does not assert an unchanging essence, any "eternal, essential and absolute something called a soul, self or atman,"[note 3] Co-ordinate to Jayatilleke, the Upanishadic inquiry fails to detect an empirical correlate of the assumed Atman, only nevertheless assumes its existence,[5] and, states Mackenzie, Advaitins "reify consciousness as an eternal self."[72] In contrast, the Buddhist research "is satisfied with the empirical investigation which shows that no such Atman exists because in that location is no bear witness" states Jayatilleke.[five]

While Nirvana is liberation from the kleshas and the disturbances of the mind-trunk circuitous, Buddhism eludes a definition of what it is that is liberated.[half dozen] [7] [note three] Co-ordinate to Johannes Bronkhorst, "information technology is possible that original Buddhism did non deny the existence of soul," simply did not want to talk nigh information technology, as they could non say that "the soul is essentially not involved in action, every bit their opponents did."[vi] While the skandhas are regarded is impermanent (anatman) and sorrowfull (dukkha), the existence of a permanent, joyful and unchanging self is neither best-selling nor explicitly denied. Liberation is not attained by cognition of such a self, but past " turning away from what might erroneously be regarded as the self."[7]

Co-ordinate to Harvey, in Buddhism the negation of temporal existents is applied even more rigorous than in the Upanishads:

While the Upanishads recognized many things as being not-Self, they felt that a real, true Self could be found. They held that when it was found, and known to exist identical to Brahman, the basis of everything, this would bring liberation. In the Buddhist Suttas, though, literally everything is seen is non-Self, even Nirvana. When this is known, then liberation – Nirvana – is attained by full not-attachment. Thus both the Upanishads and the Buddhist Suttas see many things equally not-Self, but the Suttas apply information technology, indeed non-Self, to everything.[8]

Nevertheless, Atman-like notions tin can also be found in Buddhist texts chronologically placed in the 1st millennium of the Common Era, such equally the Mahayana tradition's Tathāgatagarbha sūtras suggest self-like concepts, variously chosen Tathagatagarbha or Buddha nature.[73] [74] In the Theravada tradition, the Dhammakaya Movement in Thailand teaches that information technology is erroneous to subsume nirvana under the rubric of anatta (non-self); instead, nirvana is taught to exist the "truthful cocky" or dhammakaya.[75] Like interpretations take been put forth by the then Thai Sangharaja in 1939. According to Williams, the Sangharaja's estimation echoes the tathāgatagarbha sutras.[76]

The notion of Buddha-nature is controversial, and "eternal self" concepts accept been vigorously attacked.[77] These "self-like" concepts are neither cocky nor sentient being, nor soul, nor personality.[78] Some scholars posit that the Tathagatagarbha Sutras were written to promote Buddhism to non-Buddhists.[79] [note iv] [80] [81] The Dhammakaya Motion teaching that nirvana is atta (atman) has been criticized as heretical in Buddhism by Prayudh Payutto, a well-known scholar monk, who added that 'Buddha taught nibbana as being non-self". This dispute on the nature of teachings about 'self' and 'non-self' in Buddhism has led to abort warrants, attacks and threats.[82]

Influence of Atman-concept on Hindu ethics [edit]

Ahimsa, non-violence, is considered the highest ethical value and virtue in Hinduism.[83] The virtue of Ahimsa follows from the Atman theories of Hindu traditions.[84] [85]

The Atman theory in Upanishads had a profound impact on ancient ethical theories and dharma traditions at present known as Hinduism.[84] The earliest Dharmasutras of Hindus recite Atman theory from the Vedic texts and Upanishads,[86] and on its foundation build precepts of dharma, laws and ideals. Atman theory, particularly the Advaita Vedanta and Yoga versions, influenced the emergence of the theory of Ahimsa (non-violence against all creatures), culture of vegetarianism, and other theories of ethical, dharmic life.[87] [88]

Dharma-sutras [edit]

The Dharmasutras and Dharmasastras integrate the teachings of Atman theory. Apastamba Dharmasutra, the oldest known Indian text on dharma, for case, titles Chapters 1.8.22 and ane.viii.23 every bit "Cognition of the Atman" and then recites,[89]

There is no higher object than the attainment of the knowledge of Atman. Nosotros shall quote the verses from the Veda which refer to the attainment of the knowledge of the Atman. All living creatures are the domicile of him who lies enveloped in matter, who is immortal, who is spotless. A wise man shall strive after the knowledge of the Atman. It is he [Self] who is the eternal function in all creatures, whose essence is wisdom, who is immortal, unchangeable, pure; he is the universe, he is the highest goal. – i.8.22.2-7

Liberty from anger, from excitement, from rage, from greed, from perplexity, from hypocrisy, from hurtfulness (from injury to others); Speaking the truth, moderate eating, refraining from calumny and envy, sharing with others, avoiding accepting gifts, uprightness, forgiveness, gentleness, serenity, temperance, amity with all living creatures, yoga, honorable conduct, benevolence and contentedness – These virtues have been agreed upon for all the ashramas; he who, according to the precepts of the sacred law, practices these, becomes united with the Universal Self. – 1.eight.23.6

—Cognition of the Atman, Apastamba Dharma Sūtra, ~ 400 BCE[89]

Ahimsa [edit]

The ethical prohibition against harming whatever human beings or other living creatures (Ahimsa, अहिंसा), in Hindu traditions, can be traced to the Atman theory.[84] This axiom against injuring any living being appears together with Atman theory in hymn eight.15.1 of Chandogya Upanishad (ca. 8th century BCE),[90] and then becomes central in the texts of Hindu philosophy, entering the dharma codes of ancient Dharmasutras and afterwards era Manu-Smriti. Ahimsa theory is a natural corollary and consequence of "Atman is universal oneness, present in all living beings. Atman connects and prevades in anybody. Hurting or injuring another being is hurting the Atman, and thus one's self that exists in some other body". This conceptual connection between one'due south Atman, the universal, and Ahimsa starts in Isha Upanishad,[84] develops in the theories of the aboriginal scholar Yajnavalkya, and ane which inspired Gandhi as he led not-fierce move confronting colonialism in early 20th century.[91] [92]

यस्तु सर्वाणि भूतान्यात्मन्येवानुपश्यति । सर्वभूतेषु चात्मानं ततो न विजुगुप्सते ॥६॥

यस्मिन्सर्वाणि भूतान्यात्मैवाभूद्विजानतः । तत्र को मोहः कः शोक एकत्वमनुपश्यतः ॥७॥

स पर्यगाच्छुक्रमकायमव्रणम् अस्नाविरँ शुद्धमपापविद्धम् । कविर्मनीषी परिभूः स्वयम्भूःयाथातथ्यतोऽर्थान् व्यदधाच्छाश्वतीभ्यः समाभ्यः ॥८॥And he who sees everything in his atman, and his atman in everything, does not seek to hide himself from that.

In whom all beings have become one with his own atman, what perplexity, what sorrow, is there when he sees this oneness?

He [the self] prevades all, resplendent, bodiless, woundless, without muscles, pure, untouched by evil; far-seeing, transcendent, self-being, disposing ends through perpetual ages.—Isha Upanishad, Hymns 6-8,[91]

Similarities with Greek philosophy [edit]

The Atman concept and its discussions in Hindu philosophy parallel with psuchê (soul) and its discussion in ancient Greek philosophy.[93] Eliade notes that in that location is a uppercase deviation, with schools of Hinduism asserting that liberation of Atman implies "cocky-knowledge" and "bliss".[93] Similarly, the self-knowledge conceptual theme of Hinduism (Atman jnana)[94] parallels the "know thyself" conceptual theme of Greek philosophy.[23] [95] Max Müller summarized it thus,

At that place is not what could be called a philosophical system in these Upanishads. They are, in the true sense of the word, guesses at truth, frequently contradicting each other, nonetheless all tending in one direction. The key-note of the onetime Upanishads is "know thyself," but with a much deeper meaning than that of the γνῶθι σεαυτόν of the Delphic Oracle. The "know thyself" of the Upanishads means, know thy true self, that which underlies thine Ego, and discover information technology and know information technology in the highest, the eternal Self, the One without a 2d, which underlies the whole globe.[96]

Meet as well [edit]

- Ātman (Buddhism)

- Ātman (Jainism)

- Ishvara

- Jiva (Hinduism)

- Jnana

- Moksha

- Spirit

- Tat tvam asi

- Tree of Jiva and Atman

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b Definitions:

- Oxford Dictionaries, Oxford University Press (2012), Atman: "1. real self of the individual; 2. a person's soul";

- John Bowker (2000), The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions, Oxford Academy Printing, ISBN 978-0192800947, Atman: "the existent or true Cocky";

- West.J. Johnson (2009), A Dictionary of Hinduism, Oxford Academy Printing, ISBN 978-0198610250, See entry for Atman (self).

- Encyclopedia Britannica, Atman: Atman, (Sanskrit: "self," "jiff") one of the nigh bones concepts in Hinduism, the universal self, identical with the eternal cadre of the personality that after death either transmigrates to a new life or attains release (moksha) from the bonds of existence."

- Shepard (1991): "Usually translated "Soul" but better rendered "Self.""

- John Grimes (1996), A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0791430685, Atman: "breath" (from the verb root at = "to breathe"); inner Cocky, the Reality which is the substrate of the individual and identical with the Accented (Brahman).

- The Prescense of Shiva (1994), Stella Kramrisch, Princeton Academy Press, ISBN 9780691019307, Atma (Glossary) p. 470 "the Cocky, the inmost Self or, the life principle"

- ^ a b While often translated equally "soul," it is improve translated every bit "cocky":

- Lorenzen (2004, pp. 208–209): "individual soul (aatman) [sic]"

- King (1995, p. 64): "Atman as the innermost essence or soul of homo."

- Meister (2010, p. 63): Atman (soul)"

- Shepard (1991): "Usually translated "Soul" simply better rendered "Self.""

- ^ a b c Atman and Buddhism:

- Wynne (2011, pp. 103–105): "The deprival that a man being possesses a "self" or "soul" is probably the about famous Buddhist didactics. It is certainly its most distinct, every bit has been pointed out by Grand. P. Malalasekera: "In its denial of any real permanent Soul or Self, Buddhism stands alone." A similar mod Sinhalese perspective has been expressed by Walpola Rahula: "Buddhism stands unique in the history of human thought in denying the existence of such a Soul, Self or Ātman." The "no Self" or "no soul" doctrine (Sanskrit: anātman; Pāli: anattan) is particularly notable for its widespread acceptance and historical endurance. It was a standard belief of most all the ancient schools of Indian Buddhism (the notable exception being the Pudgalavādins), and has persisted without modify into the modernistic era. [...] both views are mirrored by the modernistic Theravādin perspective of Mahasi Sayadaw that "in that location is no person or soul" and the modern Mahāyāna view of the fourteenth Dalai Lama that "[t]he Buddha taught that [...] our belief in an independent cocky is the root cause of all suffering"."

- Collins (1994, p. 64): "Key to Buddhist soteriology is the doctrine of not-self (Pali: anattā, Sanskrit: anātman, the opposed doctrine of ātman is central to Brahmanical thought). Put very briefly, this is the [Buddhist] doctrine that human beings accept no soul, no cocky, no unchanging essence."

- Plott (2000, p. 62): "The Buddhist schools turn down any Ātman concept. Equally we have already observed, this is the basic and ineradicable distinction betwixt Hinduism and Buddhism."

- Jayatilleke (1963, pp. 246–249, from note 385 onwards) refers to diverse notions of "self" or "soul" rejected by early Buddhism; several Buddhist texts tape Samkhya-like notions of Atman c.q. consciousness being unlike from the body, and liberation is the recognition of this deviation.

- Javanaud (2013): "When Buddhists assert the doctrine of 'no-self', they accept a articulate conception of what a self would exist. The self Buddhists deny would accept to meet the following criteria: information technology would (i) retain identity over time, (ii) be permanent (that is, enduring), and (iii) have 'controlling powers' over the parts of a person. Notwithstanding through empirical investigation, Buddhists conclude that there is no such thing. 'I' is commonly used to refer to the listen/body integration of the five skandhas, but when we examine these, nosotros discover that in none alone are the necessary criteria for self met, and as nosotros've seen, the combination of them is a convenient fiction [...] Objectors to the exhaustiveness claim often contend that for discovering the cocky the Buddhist commitment to empirical means is mistaken. True, we cannot discover the self in the five skandhas, precisely considering the self is that which is beyond or distinct from the five skandhas. Whereas Buddhists deny the self on grounds that, if it were there, we would be able to point it out, opponents of this view, including Sankara of the Hindu Advaita Vedanta school, are not at all surprised that nosotros cannot betoken out the self; for the self is that which does the pointing rather than that which is pointed at. Buddha dedicated his commitment to the empirical method on grounds that, without it, one abandons the pursuit of knowledge in favour of speculation."

- Collins1990, p. 82): "It is at this betoken that the differences [betwixt Upanishads and Abhidharma] starting time to become marked. At that place is no central self which animates the impersonal elements. The concept of nirvana (Pali nibbana), although similarly the criterion according to which upstanding judgements are made and religious life assessed, is not the liberated state of a self. Like all other things and concepts (dhamma) information technology is anatta, not-self [in Buddhism]."

- McClelland (2010, pp. 16–18): "Anatman/Anatta. Literally meaning no (an-) self or soul (-atman), this Buddhist term applies to the denial of a metaphysically changeless, eternal and democratic soul or self. (...) The early canonical Buddhist view of nirvana sometimes suggests a kind of extinction-similar (kataleptic) state that automatically encourages a metaphysical no-soul (cocky)."

- ^ Williams (2008, pp. 104–105, 108–109): "(...) it refers to the Buddha using the term "Self" in order to win over non-Buddhist ascetics."

References [edit]

- ^ a b Shepard 1991.

- ^ Lorenzen 2004, p. 208-209.

- ^ Richard King (1995), Early Advaita Vedanta and Buddhism, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791425138, page 64, Quote: "Atman as the innermost essence or soul of human, and Brahman every bit the innermost essence and support of the universe. (...) Thus we can see in the Upanishads, a tendency towards a convergence of microcosm and macrocosm, culminating in the equating of atman with Brahman".

- ^ * Advaita: "Hindu Philosophy: Advaita", Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy , retrieved 9 June 2020 and "Advaita Vedanta", Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy , retrieved 9 June 2020

* Dvaita: "Hindu Philosophy: Dvaita", Net Encyclopedia of Philosophy , retrieved nine June 2020 and "Madhva (1238—1317)", Net Encyclopedia of Philosophy , retrieved ix June 2020

* Bhedabheda: "Bhedabheda Vedanta", Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy , retrieved 9 June 2020 - ^ a b c d Jayatilleke 1963, p. 39.

- ^ a b c Bronkhorst 1993, p. 99 with footnote 12.

- ^ a b c d Bronkhorst 2009, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Harvey 2012, p. 59–60.

- ^ Dalal 2011, p. 38.

- ^ McClelland 2010, p. 16, 34.

- ^ Karel Werner (1998), Yoga and Indian Philosophy, Motilal Banarsidass, pp. 57–58, ISBN978-81-208-1609-1

- ^ a b c d e Plott 2000, p. 60-62.

- ^ Deutsch 1973, p. 48.

- ^ Roshen Dalal (2010), The Religions of India: A Curtailed Guide to Ix Major Faiths, Penguin Books, p. 38, ISBN978-0-fourteen-341517-6

- ^ Norman C. McClelland (2010), Encyclopedia of Reincarnation and Karma, McFarland, pp. 34–35, ISBN978-0-7864-5675-eight

- ^ [a] Julius Lipner (2012), Hindus: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, Routledge, pp. 53–56, 81, 160–161, 269–270, ISBN978-1-135-24060-8 ;

[b] P. T. Raju (1985), Structural Depths of Indian Thought , Land University of New York Press, pp. 26–37, ISBN978-0-88706-139-iv ;

[c] Gavin D. Flood (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism , Cambridge University Press, pp. 15, 84–85, ISBN978-0-521-43878-0 - ^ James Hart (2009), Who One Is: Book 2: Existenz and Transcendental Phenomenology, Springer, ISBN 978-1402091773, pages 2-iii, 46-47

- ^ Richard White (2012), The Heart of Wisdom: A Philosophy of Spiritual Life, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, ISBN 978-1442221161, pages 125-131

- ^ Christina Puchalski (2006), A Time for Listening and Caring, Oxford Academy Press, ISBN 978-0195146820, page 172

- ^ ऋग्वेद: सूक्तं १०.९७, Wikisource; Quote: "यदिमा वाजयन्नहमोषधीर्हस्त आदधे । आत्मा यक्ष्मस्य नश्यति पुरा जीवगृभो यथा ॥११॥

- ^ Baumer, Bettina and Vatsyayan, Kapila. Kalatattvakosa Vol. 1: Pervasive Terms Vyapti (Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts). Motilal Banarsidass; Revised edition (March ane, 2001). P. 42. ISBN 8120805844.

- ^ Source 1: Rig veda Sanskrit;

Source two: ऋग्वेदः/संहिता Wikisource - ^ a b PT Raju (1985), Structural Depths of Indian Thought, State Academy of New York Press, ISBN 978-0887061394, pages 35-36

- ^ a b Grimes 1996, p. 69.

- ^ a b c Koller 2012, p. 99-102.

- ^ Paul Deussen, The Philosophy of the Upanishads at Google Books, Dover Publications, pages 86-111, 182-212

- ^ Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanishads, Oxford Academy Press, ISBN 978-0195124354, page 12-13

- ^ Raju, Poolla Tirupati. Structural Depths of Indian Thought. SUNY Serial in Philosophy. P. 26. ISBN 0-88706-139-7.

- ^ Sanskrit Original: बृहदारण्यक उपनिषद् मन्त्र ५ [IV.iv.5], Sanskrit Documents;

Translation 1: Brihadāranyaka Upanishad 4.4.5 Madhavananda (Translator), page 712;

Translation 2: Brihadāranyaka Upanishad 4.4.5 Eduard Roer (Translator), page 235 - ^ a b Sanskrit Original: बृहदारण्यक उपनिषद्, Sanskrit Documents;

Translation ane: Brihadāranyaka Upanishad 1.4.10 Eduard Roer (Translator), pages 101-120, Quote: "For he becomes the soul of them." (page 114);

Translation ii: Brihadāranyaka Upanishad ane.iv.10 Madhavananda (Translator), page 146; - ^ Max Müller, Upanishads, Wordsworth, ISBN 978-1840221022, pages XXIII-XXIV

- ^ Original Sanskrit: अग्निर्यथैको भुवनं प्रविष्टो, रूपं रूपं प्रतिरूपो बभूव । एकस्तथा सर्वभूतान्तरात्मा, रूपं रूपं प्रतिरूपो बहिश्च ॥ ९ ॥;

English language Translation 1: Stephen Knapp (2005), The Centre of Hinduism, ISBN 978-0595350759, folio 202-203;

English Translation ii:Katha Upanishad Max Müller (Translator), Fifth Valli, 9th verse - ^ a b Sanskrit Original: आत्मानँ रथितं विद्धि शरीरँ रथमेव तु । बुद्धिं तु सारथिं विद्धि मनः प्रग्रहमेव च ॥ ३ ॥ इन्द्रियाणि हयानाहुर्विषयाँ स्तेषु गोचरान् । आत्मेन्द्रियमनोयुक्तं भोक्तेत्याहुर्मनीषिणः ॥ ४ ॥, Katha Upanishad Wikisource;

English Translation: Max Müller, Katha Upanishad Third Valli, Poetry iii & iv and through 15, pages 12-xiv - ^ Stephen Kaplan (2011), The Routledge Companion to Religion and Science, (Editors: James W. Haag, Gregory R. Peterson, Michael Fifty. Speziopage), Routledge, ISBN 978-0415492447, page 323

- ^ A. L. Herman (1976), An Introduction to Indian Idea , Prentice-Hall, pp. 110–115, ISBN978-0-13-484477-0

- ^ Jeaneane D. Fowler (1997), Hinduism: Beliefs and Practices, Sussex Bookish Press, pp. 109–121, ISBN978-1-898723-60-8

- ^ Arvind Sharma (2004), Advaita Vedānta: An Introduction , Motilal Banarsidass, pp. 24–43, ISBN978-81-208-2027-two

- ^ Deussen, Paul and Geden, A. S. The Philosophy of the Upanishads. Cosimo Classics (June i, 2010). P. 86. ISBN 1616402407.

- ^ a b Sharma 1997, pp. 155–seven.

- ^ Chapple 2008, p. 21.

- ^ Osto 2018, p. 203.

- ^ Paranjpe, A. C. Self and Identity in Modernistic Psychology and Indian Thought. Springer; ane edition (September 30, 1998). P. 263-264. ISBN 978-0-306-45844-half-dozen.

- ^ a b c

- Sanskrit Original with Translation 1: The Yoga Philosophy TR Tatya (Translator), with Bhojaraja commentary; Harvard University Archives;

- Translation 2: The Yoga-darsana: The sutras of Patanjali with the Bhasya of Vyasa GN Jha (Translator), with notes; Harvard University Archives;

- Translation three: The Yogasutras of Patanjali Charles Johnston (Translator)

- ^ Verses four.24-4.34, Patanjali'south Yogasutras; Quote: "विशेषदर्शिन आत्मभावभावनाविनिवृत्तिः"

- ^ Stephen H. Phillips, Classical Indian Metaphysics: Refutations of Realism and the Emergence of "new Logic". Open Court Publishing, 1995, pages 12–xiii.

- ^ a b Plott 2000, p. 62.

- ^ a b c d Original Sanskrit: Nyayasutra Anand Ashram Sanskrit Granthvali, pages 26-28;

English translation 1: Nyayasutra run into verses 1.ane.nine and ane.i.10 on pages 4-5;

English translation 2: Elisa Freschi (2014), Puspika: Tracing Aboriginal India Through Texts and Traditions, (Editors: Giovanni Ciotti, Alastair Gornall, Paolo Visigalli), Oxbow, ISBN 978-1782974154, pages 56-73 - ^ KK Chakrabarti (1999), Classical Indian Philosophy of Mind: The Nyaya Dualist Tradition, Land University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791441718, pages 2, 187-188, 220

- ^ a b See example discussed in this section; For additional examples of Nyaya reasoning to prove that 'self exists', using propositions and its theories of negation, run across: Nyayasutra verses one.2.ane on pages 14-fifteen, i.2.59 on page twenty, 3.1.1-iii.one.27 on pages 63-69, and later capacity

- ^ a b Roy W. Perrett (Editor, 2000), Indian Philosophy: Metaphysics, Volume three, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0815336082, page xvii; likewise come across Chakrabarti pages 279-292

- ^ Sutras_1913#folio/n47/fashion/2up Nyayasutra see pages 22-29

- ^ The schoolhouse posits that at that place are five physical substances: earth, water, air, water and akasa (ether/sky/space beyond air)

- ^ a b c Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and Charles A. Moore (Eds., 1973), A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy, Princeton Academy Press, Reprinted in 1973, ISBN 978-0691019581, pages 386-423

- ^ a b PT Raju (2008), The Philosophical Traditions of Republic of india, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415461214, pages 79-80

- ^ a b Chris Bartley (2013), Purva Mimamsa, in Encyclopaedia of Asian Philosophy (Editor: Oliver Leaman), Routledge, 978-0415862530, folio 443-445

- ^ Oliver Leaman (2006), Shruti, in Encyclopaedia of Asian Philosophy, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415862530, page 503

- ^ PT Raju (2008), The Philosophical Traditions of India, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415461214, pages 82-85

- ^ PT Raju (1985), Structural Depths of Indian Thought, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0887061394, pages 54-63; Michael C. Brannigan (2009), Hitting a Residuum: A Primer in Traditional Asian Values, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-0739138465, page 15

- ^ a b c d Arvind Sharma (2007), Advaita Vedānta: An Introduction, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120820272, pages 19-40, 53-58, 79-86

- ^ Bhagavata Purana 3.28.41 Archived 2012-02-17 at the Wayback Auto

- ^ Bhagavata Purana 7.7.19–20 "Atma besides refers to the Supreme Lord or the living entities. Both of them are spiritual."

- ^ a b A Rambachan (2006), The Advaita Worldview: God, World, and Humanity, State Academy of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791468524, pages 47, 99-103

- ^ Karl Potter (2008), Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies: Advaita Vedānta, Volume three, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120803107, pages 510-512

- ^ S Timalsina (2014), Consciousness in Indian Philosophy: The Advaita Doctrine of 'Awareness Only', Routledge, ISBN 978-0415762236, pages 3-23

- ^ Eliot Deutsch (1980), Advaita Vedanta: A Philosophical Reconstruction, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0824802714, pages 48-53

- ^ A Rambachan (2006), The Advaita Worldview: God, World, and Humanity, Land Academy of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791468524, pages 114-122

- ^ Adi Sankara, A Bouquet of Nondual Texts: Advaita Prakarana Manjari, Translators: Ramamoorthy & Nome, ISBN 978-0970366726, pages 173-214

- ^ R Prasad (2009), A Historical-developmental Study of Classical Indian Philosophy of Morals, Concept Publishing, ISBN 978-8180695957, pages 345-347

- ^ James Lewis and William Travis (1999), Religious Traditions of the World, ISBN 978-1579102302, pages 279-280

- ^ Thomas Padiyath (2014), The Metaphysics of Condign, De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3110342550, pages 155-157

- ^ Graham Oppy (2014), Describing Gods, Cambridge Academy Press, ISBN 978-1107087040, folio 3

- ^ Mackenzie 2012.

- ^ Williams 2008, p. 104, 125–127.

- ^ Hookham 1991, p. 100–104.

- ^ Mackenzie 2007, pp. 100–5, 110.

- ^ Williams 2008, p. 126.

- ^ Hubbard & Swanson 1997.

- ^ Williams 2008, p. 107, 112; Hookham 1991, p. 96.

- ^ Williams 2008, p. 104–105, 108–109.

- ^ Fowler 1999, p. 101–102.

- ^ Pettit 1999, p. 48–49.

- ^ Mackenzie 2007, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Stephen H. Phillips & other authors (2008), in Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace, & Conflict (2nd Edition), ISBN 978-0123739858, Elsevier Science, Pages 1347–1356, 701-849, 1867

- ^ a b c d Ludwig Alsdorf (2010), The History of Vegetarianism and Moo-cow-Veneration in India, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415548243, pages 111-114

- ^ NF Gier (1995), Ahimsa, the Self, and Postmodernism, International Philosophical Quarterly, Volume 35, Issue ane, pages 71-86, doi:10.5840/ipq199535160;

Jean Varenne (1977), Yoga and the Hindu Tradition, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226851167, folio 200-202 - ^ These aboriginal texts of India refer to Upanishads and Vedic era texts some of which have been traced to preserved documents, but some are lost or yet to be found.

- ^ Stephen H. Phillips (2009), Yoga, Karma, and Rebirth: A Brief History and Philosophy, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231144858, pages 122-125

- ^ Knut Jacobsen (1994), The institutionalization of the ideals of "not-injury" toward all "beings" in Ancient India, Environmental Ethics, Volume xvi, Issue iii, pages 287-301, doi:10.5840/enviroethics199416318

- ^ a b Sanskrit Original: Apastamba Dharma Sutra page 14;

English Translation one: Knowledge of the Atman Apastamba Dharmasutra, The Sacred Laws of the Aryas, Georg Bühler (Translator), pages 75-79;

English Translation 2: Ludwig Alsdorf (2010), The History of Vegetarianism and Moo-cow-Veneration in Republic of india, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415548243, pages 111-112;

English Translation iii: Patrick Olivelle (1999), Dharmasutras, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0192838827, page 34 - ^ Sanskrit original: तधैतद्ब्रह्मा प्रजापतये उवाच प्रजापतिर्मनवे मनुः प्रजाभ्यः आचार्यकुलाद्वेदमधीत्य यथाविधानं गुरोः कर्मातिशेषेणाभिसमावृत्य कुटुम्बे शुचौ देशे स्वाध्यायमधीयानो धर्मिकान्विदधदात्मनि सर्वैन्द्रियाणि संप्रतिष्ठाप्याहिँसन्सर्व भूतान्यन्यत्र तीर्थेभ्यः स खल्वेवं वर्तयन्यावदायुषं ब्रह्मलोकमभिसंपद्यते न च पुनरावर्तते न च पुनरावर्तते ॥१॥; छान्दोग्योपनिषद् ४ Wikisource;

English Translation: Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, page 205 - ^ a b Sanskrit original: ईशावास्य उपनिषद् Wikisource;

English language Translation i: Isha Upanishad Max Müller (Translator), Oxford Academy Press, page 312, hymns 6 to 8;

English Translation ii: Isha Upanishad See translation by Charles Johnston, Universal Theosophy;

English language Translation iii: Isavasyopanishad SS Sastri (Translator), hymns 6-8, pages 12-fourteen - ^ Deen K. Chatterjee (2011), Encyclopedia of Global Justice: A - I, Book 1, Springer, ISBN 978-1402091599, page 376

- ^ a b Marcea Eliade (1985), History of Religious Ideas, Volume 2, Academy of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226204031, pages 493-494

- ^ Sometimes called Atmanam Viddhi, Frédérique Apffel-Marglin and Stephen A. Marglin (1996), Decolonizing Cognition : From Development to Dialogue, Oxford Academy Press, ISBN 978-0198288848, page 372

- ^ Andrew Fort (1998), Jivanmukti in Transformation: Embodied Liberation in Advaita and Neo-Vedanta, State Academy of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791439036, pages 31-46

- ^ WD Strappini, The Upanishads, p. 258, at Google Books, The Month and Catholic Review, Vol. 23, Outcome 42

Sources [edit]

- Printed sources

- Baroni, Helen J. (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Zen Buddhism, Rosen Publishing, ISBN978-0823922406

- Bronkhorst, Johannes (1993), The Two Traditions of Meditation in Aboriginal India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN978-81-208-1114-0

- Bronkhorst, Johannes (2009), Buddhist Pedagogy in Republic of india, Wisdom Publications, ISBN978-0-86171-811-5

- Chapple, Christopher Fundamental (2008), Yoga and the Luminous: Patañjali'southward Spiritual Path to, SUNY Press

- Collins, Steven (1990), Selfless Persons: Imagery and Idea in Theravada Buddhism, Cambridge Academy Press, p. 82, ISBN978-0-521-39726-1

- Collins, Steven (1994), Reynolds, Frank; Tracy, David (eds.), Religion and Applied Reason (Editors, State Univ of New York Press, ISBN978-0791422175

- Dalal, R. (2011), The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths, Penguin, ISBN978-0143415176

- Deutsch, Eliot (1973), Advaita Vedanta: A Philosophical Reconstruction, Academy of Hawaii Printing

- Eggeling, Hans Julius (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. xiii (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 501–513.

- Fowler, Merv (1999), Buddhism: Behavior and Practices, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN978-1-898723-66-0

- J. Ganeri (2013), The Concealed Art of the Soul, Oxford University Printing, ISBN 978-0199658596

- Grimes, John (1996). A Curtailed Lexicon of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English. State University of New York Press. ISBN0791430685.

- Harvey, Peter (2012), An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices, Cambridge University Press, ISBN978-0-521-85942-4

- Hookham, S. K. (1991), The Buddha Within: Tathagatagarbha Doctrine According to the Shentong Estimation of the Ratnagotravibhaga, Land University of New York Press, ISBN978-0-7914-0357-0

- Hubbard, Jamie; Swanson, Paul L., eds. (1997), Pruning the Bodhi Tree: The Storm over Disquisitional Buddhism, University of Hawaii Press

- Javanaud, Katie (2013), "Is The Buddhist 'No-Self' Doctrine Compatible With Pursuing Nirvana?", Philosophy Now

- Jayatilleke, Thou.N. (1963), Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge (PDF) (1st ed.), London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- King, Richard (1995), Early Advaita Vedanta and Buddhism, State University of New York Press, ISBN978-0791425138

- Koller, John (2012), "Shankara", in Meister, Chad; Copan, Paul (eds.), Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Religion, Routledge, ISBN978-0415782944

- Lorenzen, David (2004), "Bhakti", in Mittal, Sushil; Thursby, Factor (eds.), The Hindu World, Routledge, ISBN0-415215277

- Loy, David (1982), "Enlightenment in Buddhism and Advaita Vedanta: Are Nirvana and Moksha the Same?", International Philosophical Quarterly, 23 (one)

- Mackenzie, Matthew (2012), "Luminosity, Subjectivity, and Temporality: An Examination of Buddhist and Advaita views of Consciousness", in Kuznetsova, Irina; Ganeri, Jonardon; Ram-Prasad, Chakravarthi (eds.), Hindu and Buddhist Ideas in Dialogue: Cocky and No-Self, Routledge

- Mackenzie, Rory (2007), New Buddhist Movements in Thailand: Towards an Understanding of Wat Phra Dhammakaya and Santi Asoke, Routledge, ISBN978-1-134-13262-1

- McClelland, Norman C. (2010), Encyclopedia of Reincarnation and Karma, McFarland, ISBN978-0-7864-5675-8

- Meister, Republic of chad (2010), The Oxford Handbook of Religious Diversity, Oxford University Press, ISBN978-0195340136

- Osto, Douglas (January 2018), "No-Self in Sāṃkhya: A Comparative Expect at Classical Sāṃkhya and Theravāda Buddhism", Philosophy East and West, 68 (ane): 201–222, doi:10.1353/pew.2018.0010, S2CID 171859396

- Pettit, John W. (1999), Mipham'due south Buoy of Certainty: Illuminating the View of Dzogchen, the Great Perfection, Simon and Schuster, ISBN978-0-86171-157-four

- Plott, John C. (2000), Global History of Philosophy: The Axial Age, Volume ane, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN978-8120801585

- Sharma, C. (1997), A Critical Survey of Indian Philosophy, New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ, ISBN81-208-0365-5

- Shepard, Leslie (1991), Encyclopedia of Occultism & Parapsychology - Volume 1, Gale Enquiry Incorporated, ISBN9780810301962

- Suh, Dae-Sook (1994), Korean Studies: New Pacific Currents, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN978-0824815981

- Williams, Paul (2008), Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations (ii ed.), Routledge, ISBN978-1-134-25056-one

- Wynne, Alexander (2011), "The ātman and its negation", Journal of the International Clan of Buddhist Studies, 33 (ane–2)

- Web-sources

- ^ Atman Britannica.com, Atman Hindu philosophy

- ^ a b Atman Etymology Dictionary, Douglas Harper (2012)

External links [edit]

- A. S. Woodburne (1925), The Idea of God in Hinduism, The Journal of Organized religion, Vol. five, No. 1 (Jan., 1925), pages 52–66

- 1000. L. Seshagiri Rao (1970), On Truth: A Hindu Perspective, Philosophy Due east and West, Vol. xx, No. four (October., 1970), pages 377-382

- Norman E. Thomas (1988), Liberation for Life: A Hindu Liberation Philosophy, Missiology, Vol. 16, No. 2, pages 149-162

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C4%80tman_%28Hinduism%29

Posted by: binettewallard.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Is The Atman Related To Animals And Humans"

Post a Comment